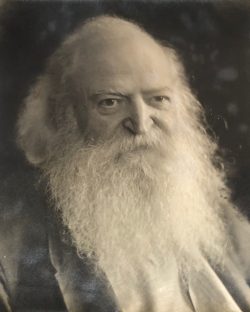

Bayard Wootten (1875-1959)

Born in New Bern, North Carolina, Bayard Wootten is one of the American South’s most significant early female photographers. She was descended from a prominent southern family; her maternal grandmother was writer and poet Mary Bayard Clarke and her father had a photography business, and galleries in Raleigh and Goldsboro. After taking classes at the New Bern Collegiate Institute, Bayard Wootten attended the North Carolina State Normal and Industrial School, now UNC-Greensboro, where she received most of her instruction in art. Wootten pursued drawing and painting in college but took up photography in 1904.

Born in New Bern, North Carolina, Bayard Wootten is one of the American South’s most significant early female photographers. She was descended from a prominent southern family; her maternal grandmother was writer and poet Mary Bayard Clarke and her father had a photography business, and galleries in Raleigh and Goldsboro. After taking classes at the New Bern Collegiate Institute, Bayard Wootten attended the North Carolina State Normal and Industrial School, now UNC-Greensboro, where she received most of her instruction in art. Wootten pursued drawing and painting in college but took up photography in 1904.

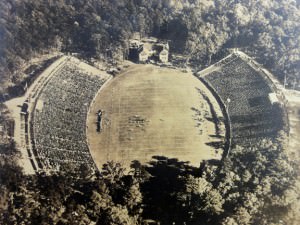

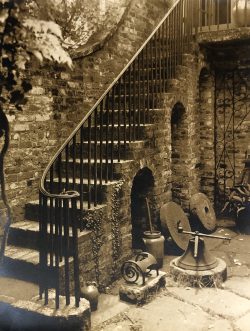

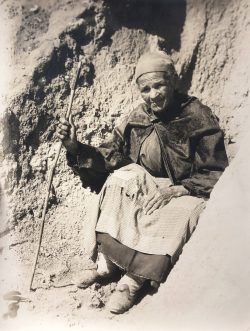

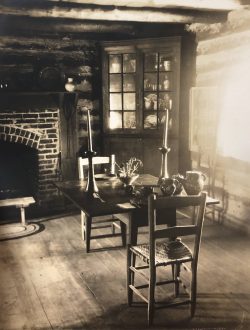

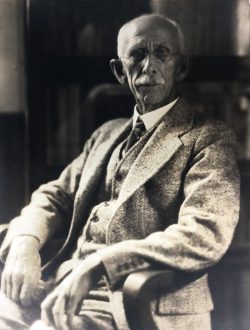

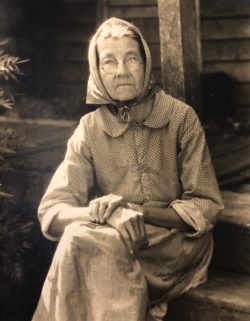

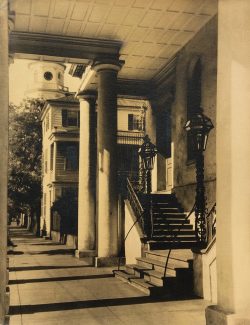

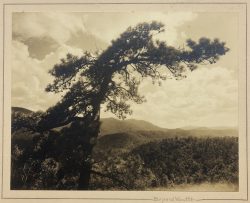

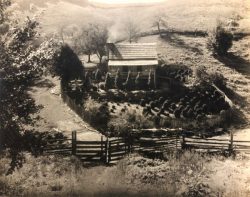

From 1928 until her retirement in 1954, Wootten operated a successful studio in Chapel Hill, managed by her half-brother, George Moulton. This arrangement allowed her pictorial style of photography to blossom. As one of the earliest photographers to use the medium as fine art, Wootten was acclaimed for her fine details, thoughtful compositions and artistic expression. Bayard Wootten is best known for her photographs from the 1930’s that demonstrate her mastery of a large range of subjects including scenes of the North Carolina Mountains, the Carolina islands and coastline, Charleston, botanical studies and images of the mountain people of the Appalachians.

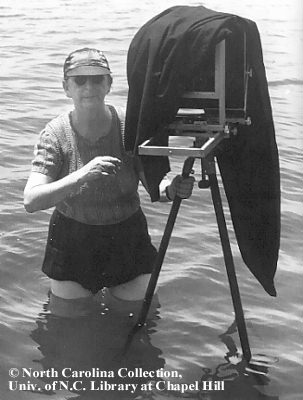

Bayard Wootten was a pioneer and an adventurer. Her remarkable career included many firsts: she designed the first trademarked Pepsi-Cola logo, she was the first woman member of the North Carolina National Guard and the first female aerial photographer in America. Over the years she had studios in New Bern, Greensboro, and New York. Wootten was a member of the Pictorial Photographers of America, and the Women’s Federation of the Photographer’s Association of America. Her photographs have been compared to the work of both Dorothea Lange and Doris Ulmann.

A number of books written in the 1930’s reproduce Bayard Wootten’s silver gelatin prints as illustrations, including Backwoods America (1934), Cabins in the Laurel (1935), and Old Homes and Gardens of North Carolina (1939). Her illustrations were also featured in Charleston: Azaleas and Old Bricks (1937), and New Castle, Delaware, 1651-1939(1939). An outstanding collection of negatives and prints by this innovative photographer is housed in the North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, UNC library, Chapel Hill.

This artist has an article

Bayard Wootten:

A real tough cookie with a long history

— By Charlene Newsom

Featured in Artsee Magazine, November / December 2010

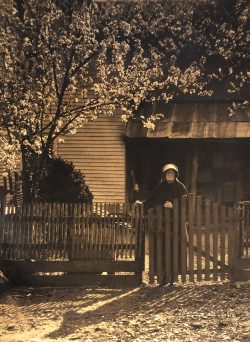

Americans enjoy stories about pioneers: courageous individuals who seek out adventure, overcome hardships, and blaze new trails. The story of North Carolina’s Bayard Wootten – nicknamed “Wootten Tootin” – is one of those inspiring tales. This pioneer female photographer – probably one of our finest – faced gender discrimination, economic hardship, divorce, single motherhood, and a devastating fire. Despite it all she left us with a legacy of breathtaking images that can still make our jaws drop today.

She was born Mary Bayard Morgan in 1875 in historic New Bern, NC, a town also esteemed as the birthplace of Pepsi-Cola. It was the rough and tumble era of the post-Civil War South. Southern families suffered many economic hardships. When Bayard was only four her father died. Her mother, also Mary, supported both her children and her own parents through decorative painting. Fancy fans, dresses and invitations were her forte. She was a clever woman who worked hard to put food on the table. She even tried taxidermy – stuffing a twelve foot alligator for a museum in Germany. This strong, resourceful, artistic woman set a sturdy example for Bayard, whose indomitable spirit would prove equal to that of her mother.

Limited money kept Bayard from completing college at the State Normal and Industrial School at Greensboro. An early failed marriage in Georgia left her stranded with two children. She returned to New Bern to paint fans and dresses with her mother. Her artistic gifts were noticed by many, including next door neighbor Caleb Bradham. When Bradham invented a drink he called Pepsi-Cola in his soda fountain shop, he asked Bayard to paint the first Pepsi Logo. The classic design was trademarked in 1903.

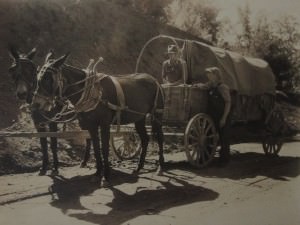

In 1904 Bayard opened a photography studio next to the family home, and it was about this time that the penny postcard was invented. When the US Postal Service authorized the mailing of these simple precursors to text messaging, Wootten joined in this early information revolution and attempted to corner the North Carolina market. She traveled the state with her camera, making a visual record of buildings, scenic views, parades, family gatherings, even disasters. In the creation of picture postcards she found a gold mine.

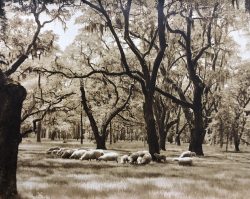

Her camera was an unwieldy box camera set on a tripod. Her films were cumbersome 8×10 glass plate negatives. She roamed her state and chronicled what she saw: the Busbees in Jugtown, mountain weavers at Penland, tulip farmers in Pinetown, strawberry pickers in Chadbourn and net haulers at Southport. In New Bern, she made history when she climbed aboard a Wright Brothers Model B airplane and became the first woman to shoot aerial photographs. Other expeditions to Tennessee, Alabama, and South Carolina resulted in timeless images of sunsets over the Ashley River, the worn faces of coal miners in Tennessee and covered bridges in the Smokies.

Her greatest output occurred during the Great Depression. While other popular photographers of the time used their cameras to advance a social agenda, Wootten swam against the tide of WPA photographers like Ben Shahn, Walker Evans, and Dorothea Lange. She was an avid pictorialist, not a documentary photographer. Her matte finish silver gelatin prints were softly focused without sharp edges. She was an artist and her photographs were personal artistic expressions.

Wootten produced landscape, architectural, and portrait photography – all as eloquent products of her unflagging persistence and keen eye. She was an honored member of the Photographers’ Association of Virginia and the Carolinas – the only woman in this male-dominated profession. She was also a proud member of the Pictorial Photographers of America (PPA).

She wore men’s clothes, liked a drink and could cuss. Her son Charles said, “Mama was a women’s liberation movement all by herself.” Wootten’s outlook was somber, but hopeful. When the Women’s Federation of the Photographer’s Association of America was established in 1908 Wootten wrote: “To be a woman and to be a photographer means to be a photographer handicapped, but this is but a transition. We are in the dawn of a new regime and the fit will survive, regardless of sex.”

Her professional career lasted fifty years. Wootten’s work appeared in six major books between 1932 and 1941. Three are in my personal library: Old Homes and Gardens of North Carolina, Cabins in the Laurel, and Charleston: Azaleas and Old Brick. Others are Backwoods America, New Castle Delaware, and From my Highest Hill. A seventh botanical work by William Lanier Hunt (1906-1996), Southern Flowers, was never published.

There are some artists who make me feel expanded and uplifted when I view their work. Bayard Wootten in one of them. She gave her subjects great meaning. Sometimes her work was imprecise, but always beautiful. In a twenty-first century world of photoshopped perfection, Wootten’s darkroom productions seem by contrast to possess an enduring quality – a genuine reality needing no enhancement.

Her collection of photographs is now held in the Photographic Archives in the Wilson Library at UNC – Chapel Hill. I also recommend Jerry Cotten’s biography Light and Air (1998).

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD

SOLD